Jane and Louise Wilson

Interviewed by Isabel Stevens

Issue 68 Autumn 2011

View Contents ▸

View Photographs by Jane and Louise Wilson ▸

Isabel Stevens: When did you first begin working seriously with photography?

Louise: We were about nineteen when we got a Mamiya C330 twin lens reflex during our undergrad. But we studied in the days when people got upset when you described your photographs as fine art.

Jane: Louise was at art school in Dundee and I was in Newcastle and we used to meet up and photograph ourselves in these mis-en-scene, tableaux sort of situations.

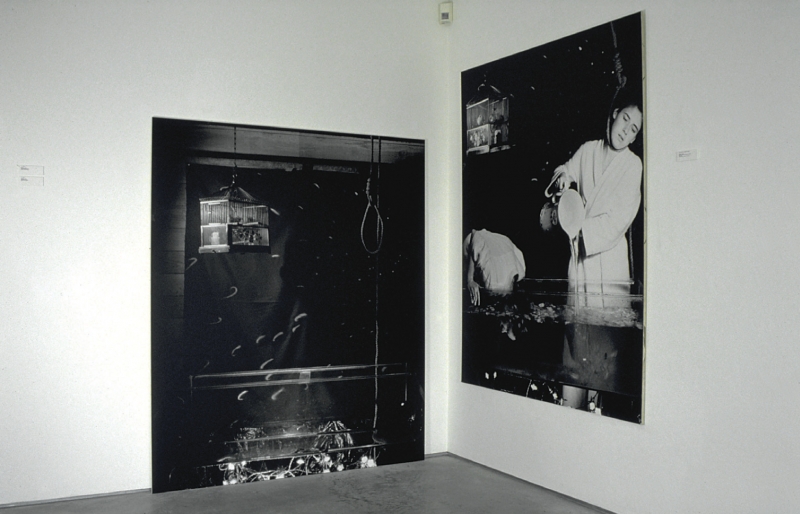

Louise: Our degree show installation was called Garage. One of the photographic panels shows Jane and I enacting a joint suicide ritual and the other panel shows the detritus after we left. It shows during and after the event.

Jane: ...or it could be before, you don’t know really – we often work with a looped narrative. We used to process our black and white photographs in garden troughs and on resin-coated paper. It was also a time when we developed our working relationship. The photographs we made were about 5x6 feet. Scale has always been a big issue in our work. And we’ve always been in interested in a kind of portraiture too. The site as well was very important even back then – the fact that it was a garage and that we’d transformed it.

Isabel Stevens: Then you moved to London and started working in your flat...

Louise: When we first came to London we lived in Kings Cross and our flat became the setting for the scenes that we were constructing.

Jane: All these very early images would be taken from similar perspectives – through the doorway and through the kitchen, but we would change the flooring, repaint bits, put polythene up, light it differently. Often the results looked like crime scenes. Were you thinking of any particular photographers at the time?

Isabel Stevens: Were you thinking of any particular photographers at the time?

Louise: Cindy Sherman of course, but also Jeff Wall. In the early 90s we were really interested in the installations of Karen Klimnick, Cathy Nolan. Jack Pierson was very interesting as well. I think we were definitely trying to bring some of that early 90s Scatter Art aesthetic into our photographic works.

Jane: We were very interested in constructing space, using a kitchen, bathroom, bedroom as a set, and staging things there. Our photographs were quite like film stills. We figured in our work less then – you might catch our feet somewhere or our arm, but it wasn’t so much a kind of portraiture. It was more about piecing together the evidence. The framing was always very important. The camera was sitting on the floor or on some stairs and because it was a twin lens reflex we always had the issue of where the point of focus was. It was a way of directing the gaze. Installation image of Garage (1989–93)

Installation image of Garage (1989–93)

Isabel Stevens: Did where you were living influence your work?

Jane: In the early 90s in London, there was a really bad recession. Kings Cross had a really transitory population and it was a pretty ropey area. This was long before its facelift. There were a lot of nefarious things going on we were always very curious about and the work we were making in our flat was very much influenced by the context we were in. While we were there, someone tried to smash in our front door and a week later they posted a note through our front door saying "I am the person who tried to smash in your front door. I have a psychiatric illness. If you want to contact me, see overleaf". You were a bit on the front line.

Isabel Stevens: And then you started renting out local B&Bs to make work in?

Jane: Yes, we used to hire a room for the weekend. We brought in all our paraphanelia – step ladders etc. – we didn’t get a peep from the owners. We were always photographing at night. It was a really intense experience because at that time everything was going on around you.

Louise: You’re in a kind of somnambulistic state – which is really good to work in.

Jane: Then we went to America and did a project called Routes 1 & 9 North in New Jersey motels along a road that used to be the main route into New York. In the motels, there were no fire exists, and the doors didn’t always lock. But there were the two of us, so we were never there on our own. Routes 1 & 9 North

Routes 1 & 9 North

Louise: We’re often drawn to these places that are imbued with a sense of collapse, that have a slightly dystopian feel to them.

Isabel Stevens: You then moved on to photograph and film in much larger spaces – the Hotel Orient in Vienna and Hanworth House among them, and then in 1996, you went to the ex-Stasi headquarters in Berlin – but this was the first time you didn’t transform the site.

Jane: The scale and sheer scope of Stasi City was a big departure in terms of what a site or location could be. The prison, Hohenschönhausen, was a memorial, so it required a different kind of engagement. We were exploring the bureaucratic spaces though – the prison had already been opened up to the public – and we had time to go back and forth. We made the work over a period of two to three months rather than overnight. Routes 1 & 9 North

Routes 1 & 9 North

Louise: The place was already imbued with such a strong sense of menace. Trying to artificially enhance that seemed inappropriate. The site had been decommissioned in 1989, but even in 1996, no one was going there. It was very interesting to be able to reflect on a space that was still hidden.

Isabel Stevens: And after that, you explored other sites relating to the Cold War.

Louise: We were interested in exploring sites in the West as well as the East. We managed to get access to Greenham Common here in the UK, which was used to house American cruise missiles. It was interesting to document it in 1998 because although it wasn’t in use, there was a still a treaty in place – you had an inspection team from Russia come to Greenham Common and teams from the West go to a comparable site in Russia.

Isabel Stevens: And you also went to Russia, to a cosmonaut training station there.

Louise: The installation Star City (2000) was filmed in Star City which is just outside Moscow where the cosmonaut training centre is. It was very utopian, this Soviet idea of creating people for the future who would live in space. We even photographed inside the hydrolaboratorium which is an entire building housing a giant pool containing a mock up of the International Space Station. It’s used for cosmonaut training as being underwater simulates the experience of a body in zero gravity. In Rising I.S.S. Hydrolaboratorium we show a submerged I.S.S. rising to meet its reflection – we shot this image, and others, through glass viewing panels below the training pool. Routes 1 & 9 North

Routes 1 & 9 North

The installation Proton, Unity, Energy, Blizzard (2000), was filmed in Baikonur in Kazakhstan which is where all the Russian space launch sites are situated and where Yuri Gagarin was launched from. One of the photographic works we made there, Proton Launch Pad was shot looking out over the Kazak steppe from behind the giant mechanical arms used to house a proton rocket pre-launch. We took a lift to reach the very top platform there which is at the summit of the launch site, very high up.

Isabel Stevens: Was it difficult to get access?

Louise: Access was difficult but Jane and I liaised through a scientist, Dr Elizabeth Bell at the British Council in Moscow whose role was to encourage collaboration between British and Russian scientists. It was just at the time that Putin had first become president, when relations between both countries were very good. We paid an ex-KGB officer in mint dollars in order for us to gain access to Star City. At that time bribes were still very common and there was quite a bit of paranoia still.

Gaining access to the Russian Cosmodrome, Baikonur in Kazakhstan was very different. Jane and I went to Moscow to meet with the Russian Space Agency – again we liaised through the British Council in Moscow – and we were simply and legitimately charged for our air fare to Baikonur and our stay in the Russian hotel there. When we met in Moscow, Jane and I took our work to show the agency to convince them to give us access, but interestingly the work they were most excited to see was the film we made in Las Vegas and not the one about the former American cruise missile base.

Isabel Stevens: A lot of the sites that you photograph are self contained entities – a lot of them are referred to as cities.

Louise: We are very interested in spaces that are microcosms.

Jane: For a long time those places were closed communities. Stasi City was at the end of a suburban street behind a wall. Star City was even more closed. It had its own infrastructure, even its own beer. And it was the same for Pripyat [a city in Chernobyl’s exclusion zone] which we visited and photographed recently – it was a very desirable place to live. It was nicknamed Atomgrad [Atomic City]. They were finishing the buildings in 1982 – it was seen as a brave new world – and the disaster happened in 1986.

Isabel Stevens: You’ve also photographed and filmed World War II bunkers in your series Sealander (2006). What attracted you to these structures and to using black and white film?

Louise: Sealander was very much inspired by the text A Handful of Dust written by J.G.Ballard in 2006. Ballard writes about the bunkers along the Atlantic Wall on the Normandy beaches. He compares the brutalist architecture’s indifference to time to that of the pyramids. We were stuck by the compelling dystopia of these modernist structures. We shot in black and white because we wanted to heighten that sense of abstraction and abandonment. In some of the images it’s difficult to work out whether the bunkers are falling into the sea or emerging from it. We felt blue skies and yellow sand would banalize the images, and normalise that sense of displaced time that we wanted to evoke. Stasi City (Operating Room), 1997

Stasi City (Operating Room), 1997

Isabel Stevens: How did you approach working in Priypiat when you went there? Can you talk a bit about your use of the yard stick – which you placed in each image and also which you made sculptures out of, in the gallery?

Jane: It was different in Priypiat, we didn’t film.

Louise: In most of our other work, the photographs became the source material, or the opening frames, for the films we made. Recently we have been more interested in photographic works that have stood alone. Here we made a conscious decision not to have them so explicitly as film stills. We didn’t want to make a film that documents the site and is about placing the viewer there.

Jane: The yard sticks were the only things that we took with us (although you’re not supposed to bring anything into the exclusion zone with you). We used them to reference measurement – because Priypiat is constantly being recorded and measured. It’s important that in all the images there isn’t a foregrounded detail. In some there are discarded shoes, and other remains. But we really didn’t want the images ro just be documentary. With the yard stick in the image you become more conscious of the fact that you’re looking. It gives the eye a point of focus. You can’t be passive, you have to be active when you’re looking at these images.

You can go through billions of images of Priypiat on Flickr. There’s certainly this concept of dark tourism, especially in relation to sites from the Cold War. Priypiat isn’t that remote, you can get a bus tour there. There is something quite touristic about photographing this site which is something we wanted to highlight.

Louise: The yard stick is roughly about six feet. It’s kind of a substitute for a figure. Working with it we were referencing a technique that’s used in set building for early films. Yard sticks were brought in as a reference to scale. It’s a cipher for a figure but it’s also an obsolete measure.

Isabel Stevens: How did you pick the locations within Priypiat to focus on?

Jane: We concentrated on the spaces for public use, swimming baths, a school, a lecture theatre, the people’s palace.

Louise: It’s interesting, when people look at the images they think they show fire damage, but there was no explosion in Pripyat. It’s actually water damage. The authorities would go into the city and spray it continuously with water to flush the dust away. What was interesting was this stripped surface that was left. The textures look almost like flesh.

Isabel Stevens: At the John Hansard gallery these photographs were exhibited alongside two other series of work: Face Scripting (2011) and The Oddments Room (2008-9). What relationship do they have with the work made in Pripyat?

Jane: The images from Facescripting are portraits of ourselves with black and white markings on our faces. They’re all about the phrenology of face recognition. You can actually now map faces, which is quite a dark concept really. The technology uses an infrared scan – you don’t have to worry about lighting. The series explores the theme of surveillance but also asks what it means for us to be documenting some of these sites. What we did for the photographs was camouflage ourselves with dazzle, a bit like they did in the second world war with ships, painting them to make them reflect onto the water. Here we were trying to confuse the camera, to make it difficult for it to measure our faces. But it’s also quite curious that the black and white paint references the black and white yard stick – formally the series are linked together.

Meanwhile for Oddments we photographed at the book hospital at the back of an antiquarian booksellers. It’s called the oddments room and it contains very rare, collectable books that are incomplete. There was something very curious about these rooms and these packages that had been left for a long time, delivered in the 1930s and remained there ever since.

Louise: They also contrast palpably with the destruction in the Priypiat images – especially the images of the schoolbooks in the classroom.

Isabel Stevens: You also placed the yard stick in these images too.

Louise: We put the yardstick in some of the images and in the others there is myself. As soon as you introduce a figure you bring an element of narrative and performance into them.

Jane: Again, the yard stick gives you a sense of scale. There’s a real feeling of vertigo there, with all those books towering up around you. That space is so compressed and collapsed.

Louise: It was a very intriguing phrase as well – the oddments room. I like the idea that one day they will be reunited...

Jane: It’s quite romantic really.

Other articles by Isabel Stevens:

Other articles on photography from the 'Documentary' category ▸