The Photographic Still Life

From the Gallery to the Lifestyle Glossy

by Gavin Murphy

Issue 19 Summer 1999

View Contents ▸

We all strive for the easy life. Often this entails finding a niche. This suggests contentment with our own limits. Questions of value are at the heart of this - how to live the good life, how to balance relations between self and the world beyond, or how to attain a satisfactory understanding of things. We seek to resolve these in the hope for comfort in our lives. Ideas of home plays a prominent role in relation to this. Home speaks of things material - a house, a garden, a retreat. It also speaks of oneness in the sense of a return to self on ending a spiritual journey. How does photography relate to all of this? I think of two areas of practice, commercial images and fine art photography appearing in the modern gallery. I wonder what it is that allows us to separate one from the other in terms of value.

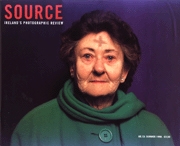

The origins of this work can be found in a casual glance, an assumption, and a recoil from that assumption. The story begins in Easons, looking for Source with its new, redesigned, colour format. Martina Mullaney's photograph adorned the cover. A soft, creamy light coloured the scene. Fresh salad and white crusty bread filled a plate. A white cup sat next to this. At a glance, it was visually seductive. It spoke of tranquil solitude and the humble pleasure of eating a fine meal in what appeared to be a delicate evening light. How close this seemed to imagery in glossy lifestyle magazines - homes with quiet atmosphere and serene airiness as a photograph captures a sunbeam on a filled fruit basket or a gentle breeze on a muslin curtain. This begged closer inspection of the image. Indeed, the bleached table, cheap crockery and a lack of any homely touch pushed against the initial seduction. Yes, this work was different. Moreover, it drew its strength from the tradition of still life and its many associations. These could range from the scrutiny of everyday life around the table and a world of domestic routine to promising silent and tranquil life through peasant simplicity; from exalting mundane life through technical virtuosity to offering a sharp reminder of the materiality of our corporal being. These were all present, ghosting my initial reading of the work.

It is a familiar stance to pitch the world of fine art against its commercial counterpart. It is due, in some respects, to a legacy of a critical avant-garde and its efforts to advance artistic and political change. If the likes of Baudrillard have alerted us to its collapse, we still nonetheless hold to a critical value fine art imagery can yield. It is rare for writing on art in Ireland to speak of art's critical impotence.

It was because of my difficulty in finding clear ground between this fine art photograph and those appearing in lifestyle magazines that I began to doubt my initial stance. Consider the cover image of Northern Ireland, Elegant: Living and Lifestyles, on display on the next shelf in the same store. The central image is a dish, classical in style, into which are placed several spherical forms. It recalls the fashionable vogue for antiquity and aristocratic decorum of the eighteenth century. As a cover image, it signals a certain refined, simple yet grand elegance. The idea is to be tasteful, not ostentatious. The written text makes clear a potential readership - a thirty-plus female homeowner. It pictures attitude and social aspiration through life around the table.

Both types of photograph then share the same terrain, namely, still life. For lavish (and slightly absurd!) displays of affluence can also be found at the heart of the still life tradition. Each adopts a position to life around the table and home. On another level, each has a concern with life among material things where the object becomes the locus of meaning. Of course there are qualitative differences. For starters, the dish is off-centre and poorly modelled. This clashes badly with the classical aspiration for elegant simplicity of form. Furthermore, the buttery tones are a bit too glaring. Mullaney's piece, on the other hand, is intriguing for the empathy it generates with its absent subject - the figure eating alone. Interestingly, empathy is attained through the viewer's relationship with the objects pictured therein.

What this suggests is that the fine art photograph may well be in a prime position to question or interrogate our relations to the material world through still life. It could also be said, however, that such a task may be complicated by the profusion of photographic imagery in lifestyle magazines (and the readings they encourage). In particular, those images, like the Elegant example, that draw upon the traditions of art as a means to bind style, pleasure and aspiration to consumption. Northern Ireland Elegant Issue 11

Northern Ireland Elegant Issue 11

Recent shifts in critical theory can be seen to turn upon this dynamic. On the one hand, there are those focusing on everyday life through fine art photography as a means of critical engagement. On the other, those focusing on consumption in everyday life now place a stress upon creativity in lifestyle choice. The question of value hangs between these positions.

Considering the first position, John Roberts, in The Art of Interruption, believes that the 'routine, commodified and alienated everyday experiences of late capitalism contain the suppressed and unformed potential of emancipatory transformation'. The question then is how a critical photographic culture can intervene so as to bring this about. A starting point for Roberts is to understand the everyday as a site of ideological struggle between both positive and negative aspects of capitalist culture. To look at the use of still life in the lifestyle glossy from this perspective, would be to expose how it promises the good life but ultimately never delivers. It merely perpetuates the cycle of commodity production. A critical practice might in contrast expose this dynamic as a means to clarify greater human need and desire. Ultimately this is a matter of political struggle.

Hugh Mackay, in Consumption and Everyday Life, adopts a different stance to this position by stressing elements of creativity in modern consumerism. Mackay comments: 'Consumption is seen as an active process and often celebrated as pleasure, and the consumer has even become elevated (by some on both the left and the right) to the status of citizen, the principle means whereby we participate in the polity.' Consumption is seen as one element of everyday life whereby cultural artefacts and their meanings are actively shaped and appropriated as potential points of identification.

Mackay sets his position against those stressing the sheer pleasure and liberating nature of consumption (J. Fiske, M. De Certeau), reminding us that for many, shopping is, more often that not, a hassle rather than a mark of independence. Nonetheless, Mackay's understanding of modern consumerist practices recognises how it involves both identification and differentiation. Goods (and imagery pushing them) can act as symbolic markers of social status, where taste distinguishes vulgarity from refinement. Taste can also be set against traditional and elitist cultural forms. In this sense, aspiration through consumerist practice can be defined creatively in as much as it is a process of negotiation, identification and appropriation. Production and consumption are read as a complex dynamic rather than sequentially, as if consumption is an end to the cycle.

To read still life photography in these terms is to understand how we can readily talk of consuming images. Those in the glossy magazines function under the realm of lifestyle choice. Lifestyle here describes attitudes to home and modern living rooted in consumerism. Since the glossy magazine is a vital point of contact between producer and consumer, the still life can be seen to function as a potential point of identification for the viewer. A viewer may choose to model their purchases for the home from the profusion of imagery, moods and atmospheres encountered. Creativity (in selecting, arranging, etc) and desire (the perfect home) are drawn closer together. This reading sits uneasily with the ideals of a critical photographic practice. It does so in as much as it challenges the assertion that consumerist practice merely perpetuates a vacuum between need and desire. le vitrail la treizième chambre d'amour Agence Vu by Bernard Faucon

le vitrail la treizième chambre d'amour Agence Vu by Bernard Faucon

It is worth drawing these ideas through some examples. I have chosen two. The first is a photograph of sunlight flowing through a curtain to a room with a bare wooden floor. A ruffled bed sheet, a rectangular form on a textured wall and a glass of water fill the space. This is the work of French photographer/philosopher Bernard Faucon. The title juxtaposes the idea of a church window to a room of love. The theme of nature, spirit and bodily union is heightened by the contrast of the intense flood of light to the room (actually refracting in the camera) with its sparse surroundings. The glass of water in this context is ripe with allusion. The image is serene with fullness of heart. Indeed, the text accompanying the image speaks of heightening the intensity of life.

Compare this to the second example. This is an interior shot focusing on a bamboo crib from Wallpaper magazine. It echoes Faucon's piece in several respects. It is an image of a sparse, yet affluent, interior (an embarrassment of riches?). It has a textured wall and bare floor. An intense band of light balances the composition. It also shares a strict symmetry and formal clarity. Again there is a serene quality to the image. The eye is drawn to the rectangular recess and the pattern of age upon the wall. There is a sense of naturalness, heightened all the more by the presence of the bamboo crib. A contrast of old and new is present in the scene. An old house is enlivened through 'tasteful' renovation, and indeed, by the presence of a crib. The allure of the image lies in visualising home in terms of material and spiritual fullness.

It is only when we look to the text that a qualitative distance opens up. Faucon's title and additional text lend poetic verve while the Wallpaper image merely states where the bamboo crib can be purchased. As images on their own, however, they each have alluring and seductive qualities. Wallpaper May / June 1997

Wallpaper May / June 1997

This is to alert us to the importance of context as an important determinant of meaning and value. And it must be understood that these images function in very different contexts and visual circuits. The Faucon work by appearing in prestigious art galleries and photographic spaces is already ascribed a sense of value on account of its selection. We may or may not agree with the choice of the curator but this is the stuff of art criticism. The point is we are expected to debate its potential merit. The Wallpaper image, however, is rarely given considered attention.

Isolating the two images and placing them together, the shared terrain is surprising. It could be said that on reading of the Faucon work, its meaning continues to resonate - perhaps to a point where the viewer is invigorated with a renewed awareness of charmed poetic life. With the Wallpaper image, there is also a degree of resonance that can survive the reader's acknowledgement of the product and the flick of the page. Allure hangs in the air, perhaps even after the purchase. This is the strength of advertising.

Consider also, the shared thematic - sparse material comfort and the preciousness of love and life. In short, this is an ideal of home: a place of refuge or retreat from the pressures of everyday living. It might even be a retreat from polity. Each promises poetry in the everyday through the enchanted realm of still life. Once again, we are alerted to the blurred terrain between the fine art photograph and its commercial counterpart.

Since images like these seep continually into the fabric of our everyday lives, what can be said of critical practice? Returning to Mullaney's piece, it has been stated that the theme of loneliness and eating alone is drawn through our relations with objects pictured therein. Here, we can see the other side of the coin, another sparse setting but this time stripped of Wallpaper's upwardly mobile urban chic. Empathy is reached when imagery and atmosphere dips below our vision of homely comfort. The ideal, with its materialist slant, still operates as a touchstone.

It would seem then, that a critique of everyday life must entail a solid investigation of debate centring on the allure of comfort and ideas of home. The life of the table and the modern interior are important points around which such themes and issues coagulate. Imagery dealing with these has been shown to draw upon an iconography and aesthetic appeal culled from traditions of art. It follows that an understanding of still life tradition as manifest in contemporary photographic practice is a crucial aspect of critical inquiry. Just as important, however, is the need to unpack the rhetorical charge of existing contemporary criticism elevating the fine art image to the detriment of its commercial counterpart. For what is at risk is an understanding of the fluid exchange between various forms of photographic practice. Perhaps by these means, it is possible to recover a sense of the complex needs and muted ideals underpinning everyday, routine activity as we build our lives among material things.

To do so, and to return finally to the Faucon image, is to grasp a sense of value beyond the weight of material acquisition. Home as transient moments born of shared intimacy, of lightness of touch, drifting space and bodily communion. Home as a locus of meaning and value. And on carrying this through the everyday, home as a matter of polity as we encounter daily the structures of power governing our lives. Would it be strange to view this as critical vision?

Other articles by Gavin Murphy:

Other articles on photography from the 'Commercial' category ▸