What Is Contemporary?

'Contemporary Photography' was at the Kerlin Gallery, 30th April - 31st May, 1999

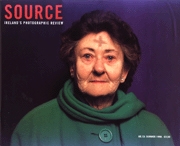

Review by Fiona Kearney

Issue 19 Summer 1999

View Contents ▸

The Contemporary Photography exhibition at the Kerlin Gallery introduces the work of five international photographers; Uta Barth, Oliver Boberg, Jeff Burton, Esko Männikkö and Walter Niedermayr. These artists have been selected 'to represent a mini-survey of current trends within international contemporary photography'. The work is indeed varied; Barth's ambient compositions, Boberg's urban sites, Burton's voyeuristic glance, Männikkö's social documentary and Niedermayr's tourist-trafficked landscapes all illustrate different strands of contemporary photographic practice. The absence of a curatorial schema, however, and the modest selection of photographs on show limits the achievement of the exhibition. The pictures offer only a glimpse of the individual oeuvres to which they belong and even their collective presentation is no more than a sliver of the international photographic scene. Nonetheless, the viewer is posed with an interesting question; what is contemporary about these photographs? Esko Männikkö, Gina and Natividad, Batesville ,1997

Esko Männikkö, Gina and Natividad, Batesville ,1997

Esko Männikkö's five prints hang sandwiched together in shabby frames that echo the run-down spaces of his Mexas pictures. The striking presentation immediately suggests his awareness of the importance of context and display. A necessary skill perhaps for a photographer working with art as a social document. This emphasis on the exhibition of the work belies the more orthodox focus of his lens. Critical awareness of the photographer's role as observer, debates about the implication of his presence and hence, a suspicion of the factual value of the photo-document have led many practitioners to pursue a different approach to the medium. It is refreshing then to encounter Männikkö's traditional vantage point, an open scrutiny of marginalised border communities in North Finland, and Mexican populations in Texas. The contemporaneity of his work lies in his ability to create rigorous compositions from this complex cultural imagery and in doing so fuse the concerns of documentary practice with a modernist organisation of photographic space. In contrast, Jeff Burton's work is more exemplary of current documentary practice - his is the fragmented, fleeting vision of much postmodern expression. The odd camera angles and cropped viewpoints may be intended to suggest a greater purchase on truth. The idea being that if photographs look as if they were taken accidentally then they are more likely to be perceived as real. The results, however, are unconvincing. Burton's work has all the right contemporary concerns - the fetishised body, the constructed gaze and kitsch sensibility - but the pictures themselves remain discarded impressions and no conceptual discourse can rescue their visual lack of engagement.

Walter Niedermayr's large panoramic vistas of the Dolomite Mountains are a comic deconstruction of the sublime landscape and a reappraisal in contemporary terms of an art historical tradition that extends from Caspar David Friedrich to Ansell Adams. The tourist tableau he captures against the imposing scenery is an entertaining commentary on late twentieth century leisure activities. The diminutive but colourfully dressed figures seem more interested in themselves and the guidebook trail, than any romantic, individual experience of nature. Oliver Boberg, Einfahut, 1998

Oliver Boberg, Einfahut, 1998

In Oliver Boberg's urban sites, there is no human presence at all. The viewer is faced with empty spaces, concrete structures and gravelled parking lots; a familiar vision of modernist architecture in decline. It is startling then to discover that these sites are in fact imaginary scale models constructed by the artist for the photographic shoot and destroyed thereafter. Boberg's capacity to create a generic modernism relies on the ubiquity of such structures within Western urban communities. His attention to detail and the meticulous recreation of a decaying facade poignantly evokes the aging process of these buildings, once the pioneering expression of Western society's idealist belief in the new. The failure of the modernist project to deliver on its utopian agenda sometimes obscures an appreciation of the formal achievement of these works. The abstract beauty of these constructed sites will perhaps prompt the viewer to see our modernist legacy in a new light.

It is Uta Barth's ethereal photograph's, however, that best capture the mood of the contemporary millenium moment. Barth's ambient compositions are created from a soft palette of blurred colours and lines, energised at points by highly reflective surfaces or points of focus. These images reference the contemporary world they depict but are more importantly animated by a visual language which looks to the twenty-first century.

Other articles by Fiona Kearney:

Other articles on photography from the 'Multi-Genre' category ▸